Oysters & Tabasco Sauce: A Perfect Match with a History

As Louisiana enters its annual oyster harvesting season, it’s worth noting that TABASCO brand Pepper Sauce owes much of its early success to oyster saloons. These culinary public houses thrived in America (and beyond) from the mid-nineteenth through the early twentieth centuries. And while the concept of the oyster bar (to use the modern term) has experienced a rebirth in recent decades, the original strain of oyster saloons all but went extinct about a century ago.

In Sex, Death & Oysters: A Half-Shell Lover’s World Tour (2009), food writer Robb Walsh — citing late oyster enthusiast and promoter Jon Rowley — wrote of America’s forgotten “culture of the oyster” when “They were plentiful, inexpensive, and ubiquitous.” As Walsh recounted, “From the 1860s through the 1920s, the oyster saloon became the epicenter of social life in America, not only in coastal regions, but also in Midwestern cities such as Chicago and St. Louis. . . .” Oysters in those days, as a result, were less a delicacy than a staple like bread, milk, or potatoes.

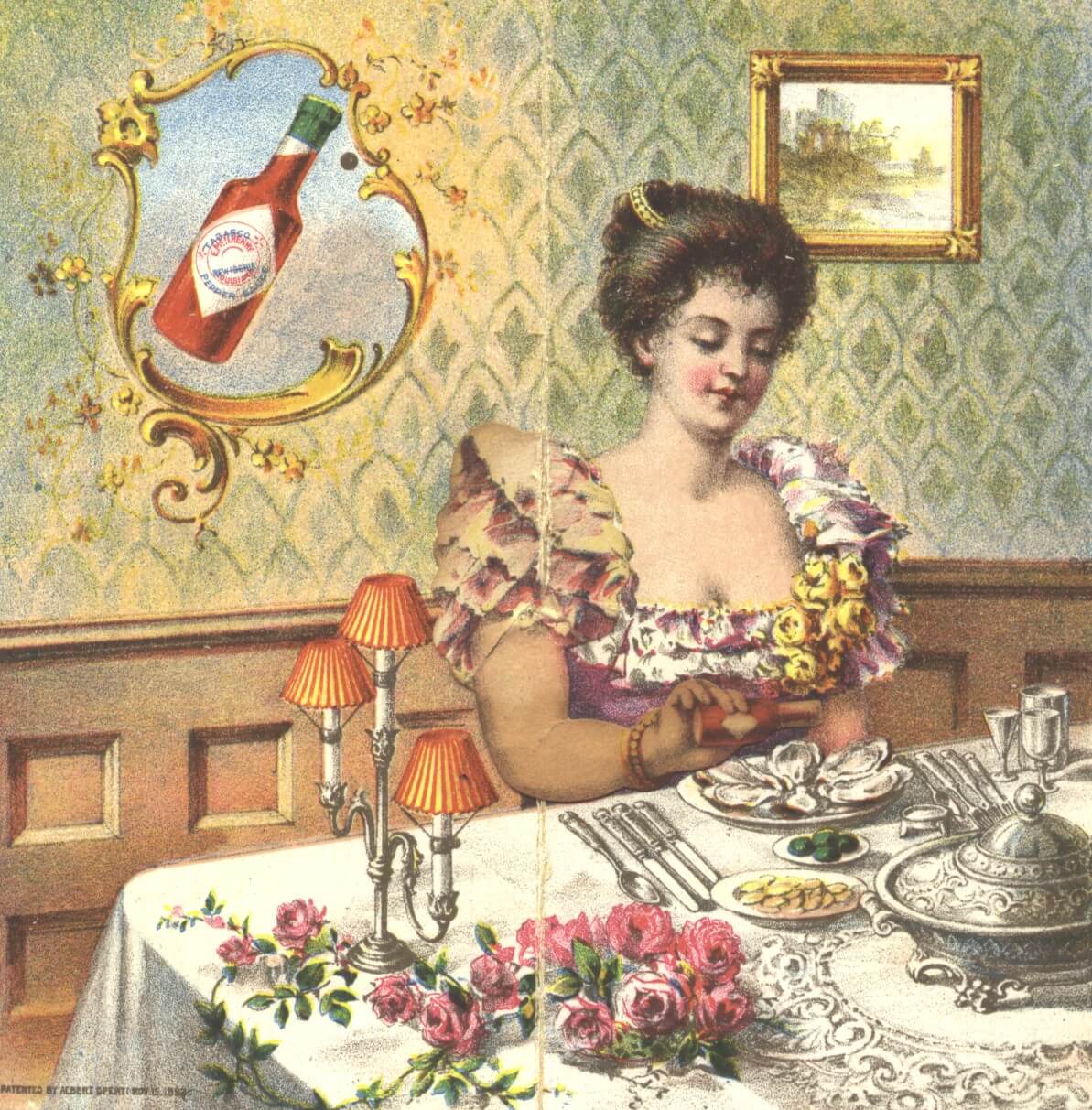

Detail of a ca. 1905 advertisement for TABASCO® Sauce aimed at oyster consumers.

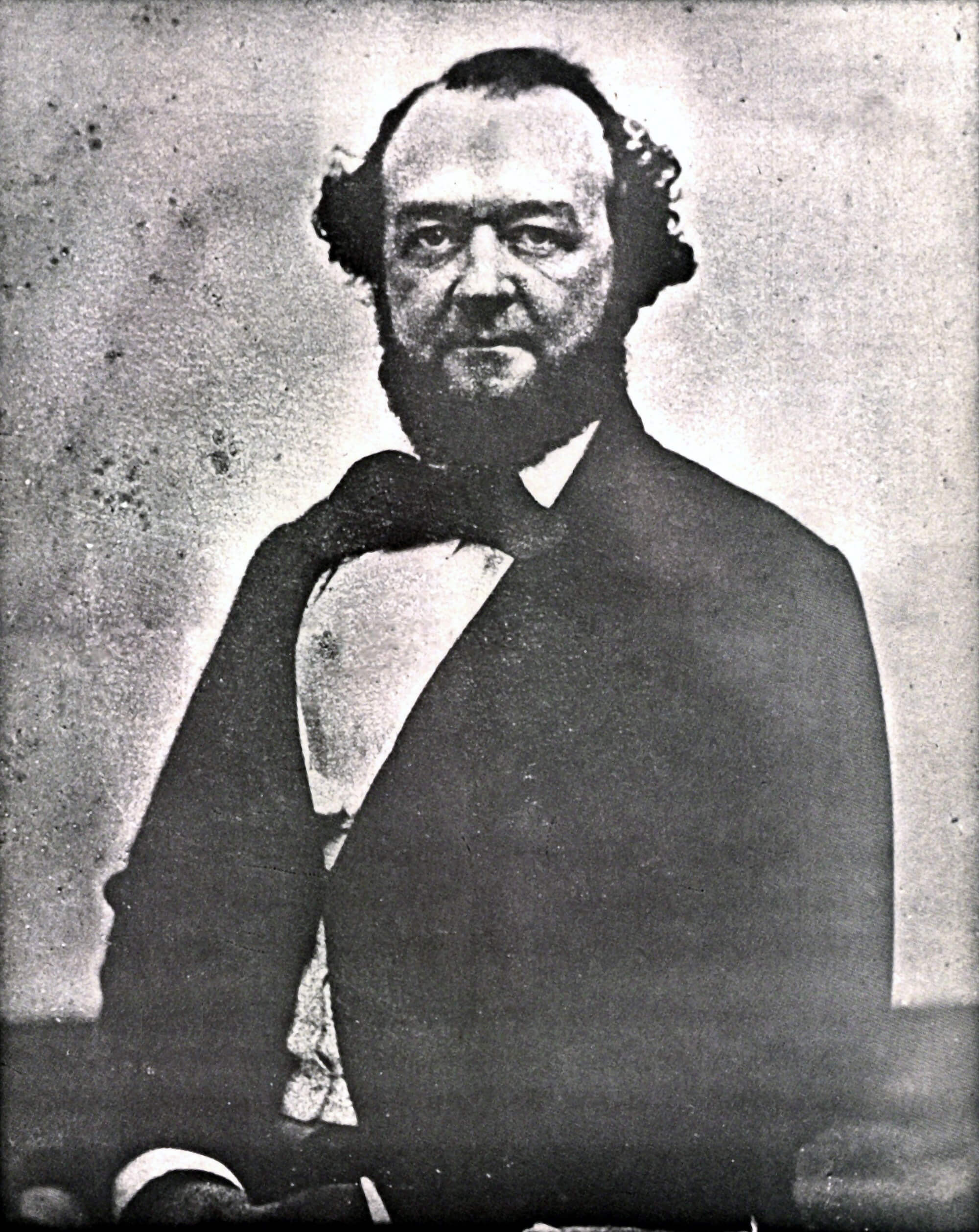

It was toward the start of that oyster heyday that Edmund McIlhenny resolved, around age fifty-three, to abandon his previous, decades-long career as a New Orleans banker to become a pepper sauce manufacturer. Some of the first consumers of his new TABASCO Sauce were oyster saloons and their voracious patrons. The earliest known reference to an oyster saloon in Edmund’s correspondence, for example, dates from February 1872. At that time his sole sales agent, former Union officer John C. Henshaw of Brooklyn, wrote him this long-winded bit of advice: “They [New York City’s leading grocers] sell to the rich, who are comparatively small in numbers, while this [TABASCO] sauce is the special want of the poorer and more numerous classes, and a thorough canvassing of the oyster saloons, restaurants, etc., by the party who has taken hold of it will[,] it is hoped[,] create such a general demand as to compel the grocers to apply for it. . . .”

Taken around 1865, this image is one of the few photographs of TABASCO Sauce inventor E. McIlhenny known to exist. (McIlhenny Company Archives)

Later that year Henshaw again counseled, “[T]here is a very large class who would be purchasers when the article became known to them and from whom a very considerable cash business may be expected. . . . I refer to the very numerous second[-] and third-rate oyster saloons and restaurants all over the city [of New York], among whom anything has yet been done to develop this promising source of demand and profit. . . . But the price and the introduction of the sauce among the oyster saloons and restaurants . . . during this season is a sine qua non [that is, a “no-brainer” in modern parlance].” Similarly, in September the St. Louis oyster, fish, and game vendor Friedheim and Klaren informed Edmund, “We will try [to sell the sauce to] all of the oyster saloons and perhaps in time it will be used a great deal more. It is one of these articles the people must acquire a taste for.”

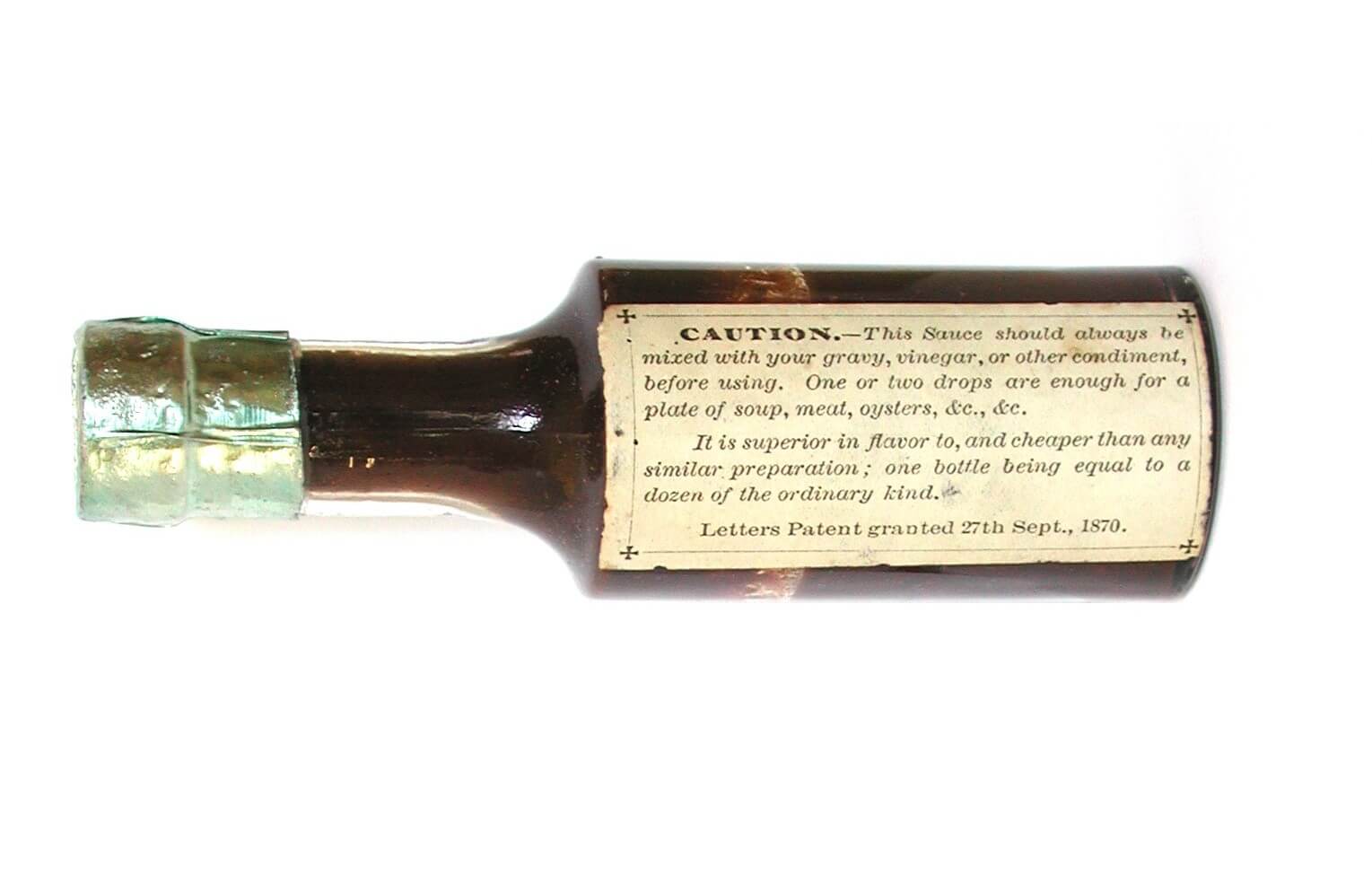

During that period, however, most consumers had yet to be introduced to TABASCO Sauce. It was, after all, a new product, first made commercially in 1868 and without recorded sales until April the next year. And because consumers had not previously heard of TABASCO Sauce, they were uncertain how to use the fiery condiment when they first encountered it. Thus, in 1872 Edmund, at Henshaw’s suggestion, printed the following notice on the back of each bottle: “CAUTION . . . One or two drops are enough for a plate of soup, meat, oysters, etc., etc. . . . one bottle being equal to a dozen of the ordinary kind.” Some consumers, however, did not get the message. In November 1874 Friedheim and Klaren reported, to quote Henshaw’s retelling to Edmund, “a countryman [rural person] in an oyster saloon a few days ago, thinking a practical joke had been played on him, dashed a bottle on the floor and offered ‘to clean out’ [fight] the proprietor and the entire concern.”

The only known completely intact early bottle of TABASCO Sauce, circa 1875(?). Note the rear “Caution label” mentioning the condiment’s use on oysters. (McIlhenny Company Archives)

By around 1900 TABASCO Sauce had become a household word throughout America. As such, it no longer had to rely on “Caution” labels — or on oyster saloons that at any rate would soon disappear. The reasons for that disappearance included overharvesting, industrial-age pollution, and attendant outbreaks of bivalve disease. These factors made edible oysters both scarcer and expensive. As a result, the oyster saloon all but vanished for generations. Meanwhile, the oyster itself ceased to be regarded as a staple and instead became what it remains today: a delicacy to be savored — preferably with a splash of TABASCO Sauce.

In 1899 grocers gave this “Victorian trade card” to consumers as a collectible. When the card was opened and closed, the woman’s arm moved up and down as if she were dousing her oysters with TABASCO Sauce. (McIlhenny Company Archives)

Shane K. Bernard, Avery Island, Louisiana

Holding a Ph.D. in History, Bernard has served as historian and curator to McIlhenny Company for over twenty-five years. He is the author of Tabasco: An Illustrated History and several books about Cajun and Creole history.

Sources:

Robb Walsh, Sex, Death & Oysters: A Half-Shell Lover’s World Tour (Berkeley, CA: Counterpoint, 2009), p. 200-201; John C. Henshaw, Brooklyn, NY, to E. McIlhenny, Petite Anse Island [Avery Island]/New Iberia, LA, 24 February 1872 and 12 November 1874, signed handwritten letters, E. McIlhenny Collection, McIlhenny Company Archives, Avery Island, LA; John C. Henshaw, Brooklyn, NY, to E. C. Hazard and Co., New York, NY, 25 November 1872, signed handwritten letter, E. McIlhenny Collection, McIlhenny Company Archives, Avery Island, LA; Friedheim and Klaren, St. Louis, MO, to Edmund McIlhenny, New Iberia, LA, 16 September 1872, signed handwritten letter, E. McIlhenny Collection, McIlhenny Company Archives, Avery Island, LA.

For information on the decline of oyster saloons see Andrew F. Smith, Food and Drink in American History: A “Full Course” Encyclopedia, Volume 1: A-L (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2013), p. 639 (s.v. “Oyster Bars”); and Barbara Brennessel, Good Tidings: The History and Ecology of Shellfish Farming in the Northeast (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 2008), p. 3.